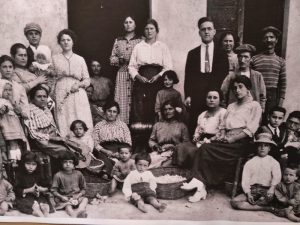

Back in the old days, at the end of April the farmers had quite a big job in preparing the brigattiera, the place in which the silkworms were producing their silk. The job consisted in setting up two or three rows of poles, which with their arms supported the sturòli (kind of long mats made of reeds, prepared during the winter), on which the silkworms could be fed. It was usually the women who took care of the animals, and some old women still nowadays tell stories about the loud smacking sound of the caterpillars while eating. We are not speaking about Chinese tradition of silk, but the one coming directly from Le Marche! Italy was even the largest silk producer in all of Europe from the 13th century.

Back in the old days, at the end of April the farmers had quite a big job in preparing the brigattiera, the place in which the silkworms were producing their silk. The job consisted in setting up two or three rows of poles, which with their arms supported the sturòli (kind of long mats made of reeds, prepared during the winter), on which the silkworms could be fed. It was usually the women who took care of the animals, and some old women still nowadays tell stories about the loud smacking sound of the caterpillars while eating. We are not speaking about Chinese tradition of silk, but the one coming directly from Le Marche! Italy was even the largest silk producer in all of Europe from the 13th century.

Jesi was a real important centre for silk production in Italy starting from the 19th century and also for the first strike ever headed by Gemma Perchi to request a 8-hours day.

Gelso

The main reason for a big silk production in Jesi is connected to the need of water: Jesi had many natural springs in the area. The farmers supplied the industries with the silkworm cocoon. The basic material, the silkworm cocoon, was supplied by the farmers in the area. What did the silkworms eat? Mainly mulberry leaves, hence the tradition of “doing the fronna”, i.e. the picking up of leaves from the mulberry tree.

But how did the heavily guarded Chinese secret get to the peninsula? It was probably monks who secretly smuggled some silkworms from China and then donated them to the Byzantine emperor Justinian in the 6th century AD.

Silk is made from the cocoons of silkworm caterpillars: silk moths are a butterfly species whose eggs hatch silkworms. About 1-2 months after hatching, the caterpillars spin a cocoon of silk thread coming from one of their body glands. In this cocoon the caterpillar pupates and hatches again after about 1 week as a butterfly.

In silk production, these cocoons were killed with hot water and the material was released to spin silk threads. These were then processed into fabrics in northern Italy.

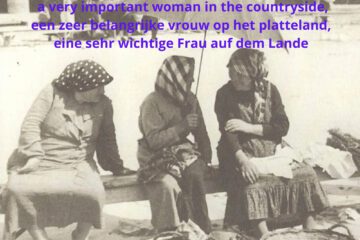

Jesi was the centre of this production because it had more than 30 spinning mills at the beginning of the 20th century! Isabelle and Elke recently had the opportunity to take a guided walk through Jesi that showed them the work done mainly by women and little girls. Child labor was already forbidden at the beginning of the 20th century, but most families were rich in children and very poor. During any inspections, the girls hid in the director’s house or under the long skirts of the adult workers. The work was hard, long and underpaid. There was someone who had to boil the water in which the cocoons were made so that the caterpillars died, someone had to take the cocoons out at the right time and then the spinning process started and the silk threads were formed ….. they were not allowed to be thin and not too thick because that could lead to hefty fines. The silk threads were then usually transported to the textile factories in the north of Italy.

Jesi was the centre of this production because it had more than 30 spinning mills at the beginning of the 20th century! Isabelle and Elke recently had the opportunity to take a guided walk through Jesi that showed them the work done mainly by women and little girls. Child labor was already forbidden at the beginning of the 20th century, but most families were rich in children and very poor. During any inspections, the girls hid in the director’s house or under the long skirts of the adult workers. The work was hard, long and underpaid. There was someone who had to boil the water in which the cocoons were made so that the caterpillars died, someone had to take the cocoons out at the right time and then the spinning process started and the silk threads were formed ….. they were not allowed to be thin and not too thick because that could lead to hefty fines. The silk threads were then usually transported to the textile factories in the north of Italy.

The spinning mills in Jesi came extensively in the news in the early 20th century and mainly after the First World War because in 1919 the workers all acquired the 8-hour day after weeks of struggle and strikes. The person behind it was Gemma Perchi, a very brave, resolute woman who could convince all workers, more than 1,000, to have such a long strike, knowing that they would not earn any money. She had already caused a working hour drop from the original 14 hours a day to 9 hours. A huge victory, especially when you consider that they were the very first workers (also in Europe) who managed this.

The spinning mills in Jesi came extensively in the news in the early 20th century and mainly after the First World War because in 1919 the workers all acquired the 8-hour day after weeks of struggle and strikes. The person behind it was Gemma Perchi, a very brave, resolute woman who could convince all workers, more than 1,000, to have such a long strike, knowing that they would not earn any money. She had already caused a working hour drop from the original 14 hours a day to 9 hours. A huge victory, especially when you consider that they were the very first workers (also in Europe) who managed this.

We are now exactly 100 years later and on 1 May this event was proudly commemorated.

The entire silk production collapsed completely in the 1950s, not because of competition or because things were going badly, but because of a lack of basic material. After all, the workers were still financially exploited, but also the farmers who supplied the cocoons received little money for the raw material. Then when factories were created everywhere and employment increased, people preferred the better paid factory life to struggling for an arm’s wage. No more silkworms therefore meant no more silk.

1 Comment